Table of Contents

Ask any educator about the most challenging time of year and you’re likely to get a response related to state or district testing. While we all understand the need for annual assessments as a measure of progress, students and staff often experience heightened stress during “testing season.” Along with the disruption to regular routines, many students experience test-related anxiety.

What Is Test Anxiety?

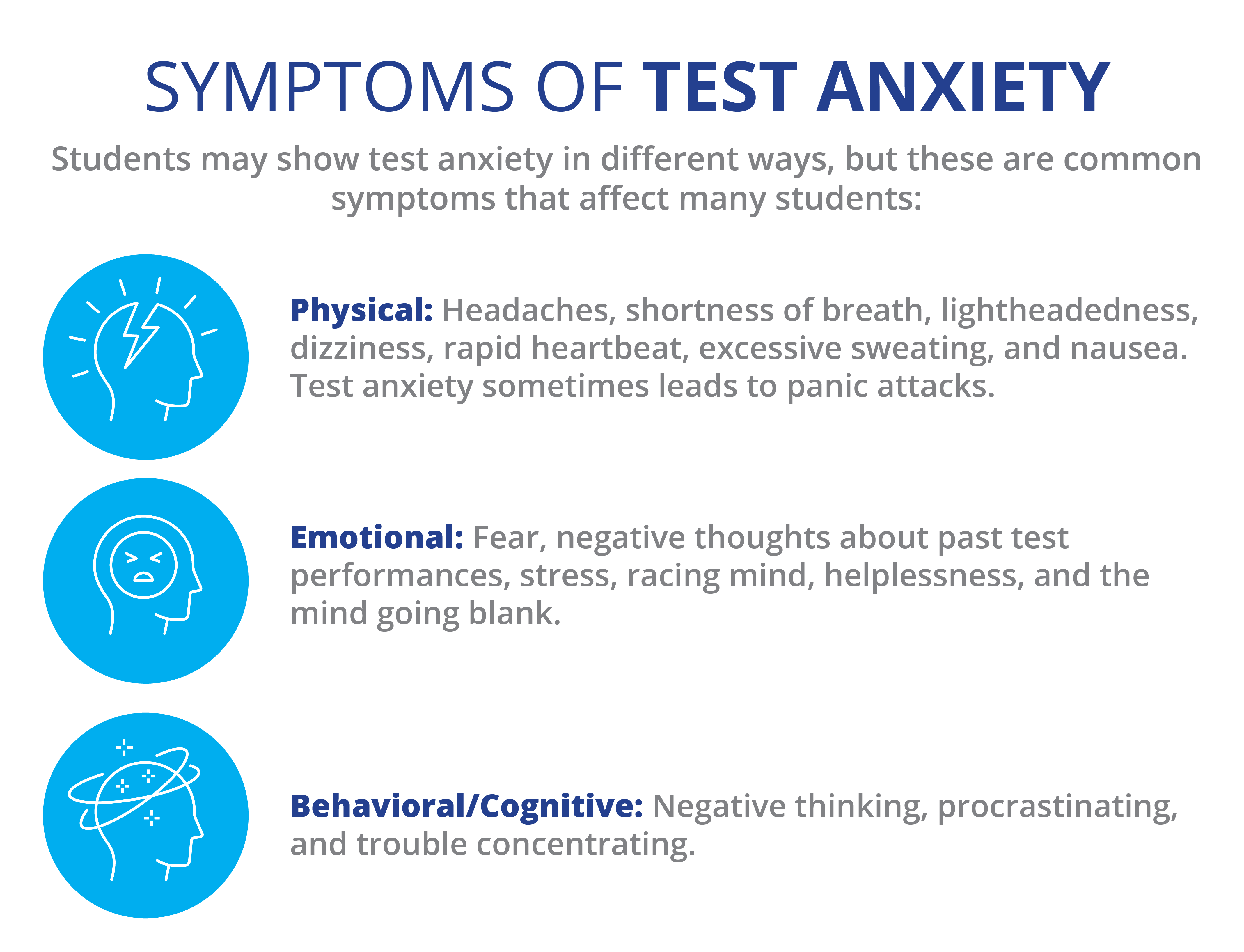

Test anxiety is a combination of physical and emotional symptoms that hinder a student’s ability to perform well on tests. Test anxiety can affect students for a variety of reasons: previous poor performance, struggles with academic content, family pressure, attention issues, possible mental health issues, and other factors. Test anxiety is real and can turn an already nerve-wracking experience into something unbearable.

What Causes Test Anxiety?

Perhaps the most common cause of test anxiety is the fear of failure. Why would an otherwise high-performing student experience this fear during a test? Students often assign unrealistic value and consequences to an exam, leading to damaging thoughts such as “If I don’t do well on this test, I’m going to fail the class,” “My parents are going to be disappointed in me if I don’t get an A,” or “I’ll never get into college if I fail this test.”

While these feelings may seem hyperbolic or dramatic to us, they’re certainly not to the student at the time of the test. In some cases, a student may actually need to achieve a certain grade on a test to pass the class or get a higher grade, and that places a massive amount of pressure on them. Similarly, some students place very high expectations on themselves, resulting in pressure and test anxiety.

When students aren’t prepared for a test, because they didn’t study or waited until the last minute to, they often become overwhelmed and experience anxiety. Sometimes, however, students do put in the time to prepare and study yet still perform poorly on an exam. This often leads to negative feelings about future tests and damages student confidence.

Luckily, there are some steps that educators can take to reduce and even overcome test anxiety for their students.

How to Overcome Test Anxiety

Test anxiety can be a challenge to overcome, but there are strategies and methods to help students relax and feel confident and comfortable during an exam.

1. Build Students’ Self-Confidence

The higher a student’s self-confidence, the lower the likelihood of test anxiety. Educators can help students build their self-confidence in several ways, including:

- Integrating resilience supports into daily instruction. Every day, educators can look for and capitalize on opportunities to teach and reinforce resilience competencies that will help students build their self-confidence. Examples include:

- Emotional regulation:Ask students to rate their feelings on a “mood meter” or other visual representation of emotions and identify step-by-step strategies for moving from one mood (e.g., “afraid”) to another (e.g., “calm”).

- Identifying strengths:Ask students to identify one thing they like about themselves and one thing they like about each of their classmates, then share their lists. This builds skills around self-identifying strengths and self-confidence.

- Coping and tolerance skills:Ask students about a challenging experience they face (e.g., waiting in a long line, going to a doctor’s office) and have them identify ways they can make that experience easier for themselves. Then, ask how they can use those skills for different challenging experiences.

- Maintaining a positive attitude:Ask students to identify things, people, or experiences that make them happy and identify ways they can access that happiness in the face of challenging situations.

- Community building. Students who feel like they’re part of a larger community (i.e., classroom or school) feel less isolated, more supported, and more confident. Educators can hold dedicated time for building classroom community where students discuss strengths, share fears, and prepare together for upcoming challenges.

- Reminding students about accommodations. Students with disabilities may experience more test anxiety than their peers without disabilities. It may be helpful to remind them of the accommodations they can access, if applicable (e.g., extra time, scheduled breaks, an environment with limited distractions). This can create a sense of autonomy and empowerment, which can improve self-confidence.

- Teaching healthy habits. Students who feel better are likely to feel more confident, so embedded instruction in healthy habits related to nutrition, sleep, and exercise can be a helpful focus for educators.

2. Build Fluency with Test-Taking Strategies and Skills

Most of us feel more confident when asked to perform a task with which we already have some degree of familiarity. We can help students practice the skills they’ll need for test-taking in low-stress, supportive environments before they sit for an actual test. Strategies include:

- Building behavioral momentum. Formal assessments often require a lot of sitting quietly without a break, which can be a challenge for anyone – and especially for younger students, students with challenging behaviors, or students with disabilities. Build students’ endurance in the months leading up to test day by having daily or weekly 5-minute practice tests, then increase to 10, then to 15, working up to the eventual length of the tests. Incentivize successful completion and appropriate behavior.

- Role play test day. Have students do a “mock” test day and practice all relevant routines: having the correct writing utensils, the rules for breaks, and expectations for behavior. Celebrate a successful trial run with a class-wide activity or game.

- Make test preparation fun. When reviewing for the big test, use a variety of games (e.g., Jeopardy, Kahoot!) to review, set up mini-competitions, and have students quiz each other. Students can choose their own partners or groups to build social skills and comfort with the materials; staff can also designate peer mentorship dyads to build fluency and have students trade off being the leader of the preparation activity.

3. Integrate Test Preparation into Daily Behavioral Supports

The more that test preparation and test day feel like a regular part of the school routine, the less anxiety and stress created for students (and staff!). Integrating test preparation into existing positive behavioral supports can look like:

- Including expectations for test-taking in behavioral matrices. For example, if your schoolwide expectations include “Be Responsible” or other broad categories of behavior, you can define those expectations for test-taking routines. “Being Responsible” during “Test Taking” could be sitting quietly, having the desk cleared of all other items, and raising hands to get the teacher’s attention; “Ready to Learn” for “Test Taking” could look like getting to the test a little early, bringing your pencils, and following directions carefully.

- Design reinforcement opportunities related to meeting test-taking expectations. Consider designing specific incentives related to test-taking. For example, have a special “Do Your Best on the Test” raffle where students earn tickets for being on-task, engaged, and for checking their work during any test preparation and the test itself. The raffle could be at the classroom or school level, depending on the size of your program and resources available.

- Use behavior-specific praise to acknowledge students meeting the test-taking expectations. When students apply the expected test-taking behaviors, provide specific and contingent praise statements that explicitly mention the behavior observed. For example: “Ben, great job arriving early and sitting down quietly – I see you’re ready!” Or “I saw everyone at this table check their work before putting their pencils down – awesome!”

- Model the behaviors you want to see. Test season can create anxiety and stress for staff, too. We can help create a calm, comfortable environment by accepting that testing – whether high-stakes or a weekly spelling quiz – is part of the learning experience and by helping prepare students for the content and the behaviors they’ll need to be successful. When students express feeling anxious, we can validate (“I hear you saying this is tough for you”), remind them of any coping and tolerance strategies that we’ve taught, and continue to implement our regular behavior supports and other routines to the greatest extent possible so students feel grounded and surrounded by what’s familiar.

Tips for Effective Studying

By preparing for an exam the right way, students can head into any test feeling confident and free of stress. Share these tips with your students to help them learn how to study efficiently.

- Prepare yourself by knowing what material will be covered on the test, as well as the format of the test (true/false, essay, multiple choice, etc.). If you’re not sure, ask your teacher whether recent quizzes, homework assignments, and class notes will be included.

- Make flashcards and other study aids that help you practice more effectively before an exam.

- Study each day ahead of the test, even if it’s only for a short time. This will keep you familiar with what will be on the test and provide you with plenty of practice time ahead of the exam.

- Maintain focus and take breaks. Make sure you’re studying in a distraction-free environment (turn off phones and devices…or leave them in another room) so you’re fully focused on your studies. And take breaks every 30 to 45 minutes to stay refreshed.

- Give your study aids one last look the day of the test to make sure the material is top of mind.

How SESI Can Help

While we may not be able to get everyone excited about and looking forward to upcoming tests, we can set up the environment to increase the likelihood of success and decrease the likelihood of stress and anxiety. For students with more intensive test anxiety, talking with a SESI social worker or counselor to develop a plan (in addition to the strategies mentioned above) can also be helpful.

Hopefully, some of the skills students learn as they prepare to take school tests will generalize to high-stakes assessments later in life: they may be calmer during a driving exam, college entrance exam, or licensing exam. Learning how to cope with and tolerate stressful situations is a valuable life skill, and helping students learn those relevant behaviors while they’re in school can prepare them for similar situations in the future.